Stephanie Torres is eight months pregnant, but unlike many other expecting working mothers, she has no upcoming maternity leave. And no steady paycheck to rely on. But she does have an eight and a half-foot albino python, and an alluring stage name, “Serpentina.”

A member of the Coney Island Sideshows by the Seashore cast since 1998, Torres earns a living as a snake charmer and continues to seek work even as her due date approaches.

This past Saturday night she performed at an event to benefit the Boys and Girls Club in Asbury Park, New Jersey, with other members of the Coney Island show. She also intends to entertain at the upcoming Coney Island Spring Gala in New York City this weekend.

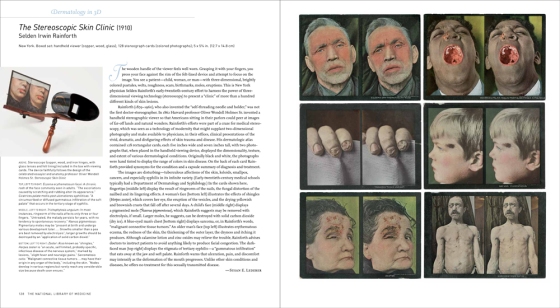

Serpentina and Pee-Wee Porterhouse. Photo courtesy of Stephanie Torres.

Since first taking the stage with Sideshows by the Seashore, Serpentina has charmed several serpents and built a rapport with each over the years, allowing her to sync her movements to the snake’s. In a typical performance, Torres — who towers at 5′-10″ and has a bifurcated tongue — dances with her slithering partners as it moves “this way and that way” to the music. Much of their choreography occurs from her knees. “The balance is easier when I have the snake up in the air,” Torres explains.

Holding the snake aloft as she kneels, Serpentina will seductively bring its face to hers as she bends backward — a feat she still pulled off successfully just days ago with the debut of a new four and a half-foot long albino python, Pee-Wee Porterhouse, at the Asbury Park show. “I was surprised and excited about it,” she says. Her recently retired partner, Firecracker, was also an albino python. In her experience, that particular breed is livelier on stage than others.

After three to five minutes, her shows typically end by affectionately drawing the serpent’s head into her mouth for a kiss. However, due to the Salmonella carried by snakes, that’s one part of her performance that’s changed during her pregnancy. “I don’t have proof, but I think I’ve developed immunity, but I don’t want to take a chance with the baby,” she says.

Other than that, she’s had no worries about her unique line of work. “Concerns about the snake getting aggressive or hurting me haven’t gone through my mind.”

Her boyfriend, Tim Porter, who earns his living as a welder and carpenter, is supportive of her career and continued work. “He think it’s cool,” she says. “He thinks it’s sexy.”

Winter bookings, however, aren’t in abundance for a snake charmer. Not only is it a slow season, but Torres hasn’t dedicated the usual time to pursue gigs because she’s been preoccupied readying her house for the baby — a boy to be named Gunner Steel Porter.

Baby proofing is something all expectant parents go through, to differing degrees. But Serpentina’s is a bit unique. She and Porter keep three snakes and three dogs in their home. At nearly nine feet, and weighing 30 pounds, Firecracker is the largest. It should be noted his full name is Firecracker Von Voom — a promotion from his original name, Cracker. “He started biting people, so I said I think we need to change it to Firecracker,” Torres explains. “Firecracker Von Voom.”

She had performed with him since 2007, but respiratory problems forced Firecracker to retire from the stage. His roommates include his replacement, Pee-Wee Porterhouse, and a California red-tailed boa called Pancho McBride, which belongs to Porter.

Their canine counterparts include a Chihuahua, a Chihuahua Yorkie mix and a large mutt. “Firecracker could eat both of the Chihuahuas,” Torres says. “You have to keep them well fed to keep them calm. I keep them on a regular feeding basis. That’s very important.”

The snakes live in the bathroom in individual terrariums, but will be moving into an empty guest bedroom. “Once they’re in the bedroom, we’ll padlock the door so once the kid starts walking around he can’t get curious,” Torres says.

Then, of course, there’s the baby’s room. They’ve already painted the walls to look like metal panels with rivets. “Like Gru’s lab from Despicable Me,” she says.

This spring, Serpentina will no longer be part of the Coney Island Sideshow cast, but she intends to continue snake charming independently. A few gigs a week earns enough income for her to live.

“It will be nice because I can spend more time with the baby once he’s here,” Torres says. “It’s better than a nine to five.”

© Marc Hartzman