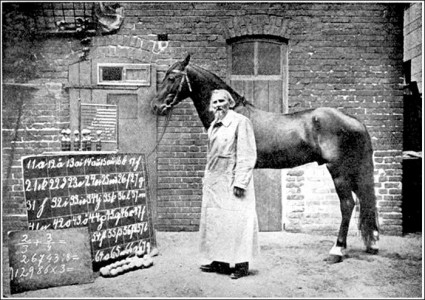

In 1904, a nine-year-old horse called Hans trotted through performance halls in Berlin astounding crowds with his uncanny mental agility. His owner, Herr Wilhelm von Osten, was a former schoolteacher and educated his horse to the level of a child the same age. Or so he claimed. The Orloff stallion learned to spell, do math, recognize people from photographs, differentiate between colors and music, and answer various questions. All Hans had to do was tap his right front hoof once to denote one, twice for two, and so forth. Letters were signified in the same manner, one tap corresponding to A, two taps to B. Hopefully Hans wasn’t asked to spell too many words with the letters Y and Z.

Von Osten’s horse also boasted an elephant-like memory. In one demonstration, Hans was introduced to a Count Dohna. He was told, “That is Count Dohna.” Thirty minutes later the Count was pointed to and von Osten asked Hans his name. The horse walked up to a blackboard filled with the letters of the alphabet and picked out D-o-h-n-a. Another stunt involved members of the audience who would offer the stallion photos of themselves, then line up in front of him. Von Osten would show Hans a photo and have him point out that person in the line. This proved as easy for the horse as for any person.

Clever Hans dazzled audiences and puzzled scientists. Brilliant minds studied the horse, trying to learn whether it was all a trick or if the horse was in fact educated. The most obvious test was to learn if Hans could still perform without von Osten present. According to one article, the answer was yes: “It is understood that the animal has answered questions and figured arithmetical sums when his instructor has not been near.”

The skilled stallion even managed to cause a political rift in Prussia. One of Hans’ enthusiastic fans happened to be the Prussian Minister of Education, Dr. Studt. Studt was so taken by the animal that he wished to have him perform before Emperor William. However, the other ministers objected. Frustrated by the opposition, Studt threatened to resign from his position, but eventually came to his senses and stayed with the Ministry. Otherwise, this could have been the first horse to cause a split in a government.

Hans became an international sensation. In an article about talented circus horses, one American journalist said of Hans: “Berlin, however, has an animal of the species now on show which has gone beyond precedent in cultivation and exhibits phenomena of cerebration out of all parallels.” Dr. William T. Hornaday, Director of the Bronx Park Zoological Gardens, was equally impressed. In his 1922 book, The Mind and Manners of Wild Animals, he wrote that Hans “was a phenomenon, and I doubt whether this world ever sees his like again. His mastery of figures alone, no matter how it was wrought, was enough to make any animal or trainer illustrious.”

Even The New York Times was caught up in the Hans hype. There was hope and expectation that the horse’s education would advance to the point where he would actually learn to speak—becoming a true Mister Ed. The Times writer said of Hans’ potential for language:

“[Hans] has not got so far as that yet, but is well on toward it, and before the cold weather sets in may be able to hold discourse with his beleaguering professors in some dialect that both can understand. It would be mortifying to discover that its kind still kept so poor an opinion of us as that held by Swift’s cultivated and conversible houynhnhms. But considering that the most pretentious of our species cut their tails and manes off for fashion’s sake and torture them in various ways to promote attitudes and motions of style, while the brute of our species heaps on them all manner of cruelty and ill, it would not be at all surprising if they did so.”

He had a point, if horses could talk, they would justifiably have a lot of complaints.

Science, however, was not about to accept that a horse could possess the intelligence of a small child. Several German scientists were determined to expose some form of trickery. Ultimately, the director of the “Psychological Institute” of the Berlin University, Professor Oskar Pfungst concluded that Hans only knew the answer if the person asking the question knew the answer. In studying the horse, Pfungst confirmed that it could answer questions without von Osten present. Hans was able to answer whatever Pfungst asked. Still, a horse could not possibly possess this sort of intelligence. Rather, Pfungst realized the horse had a remarkable ability to perceive signals from the questioner, despite his efforts to remain still. Hans was detecting sign whether they were conscious or unconscious. When Pfungst asked a question, he recognized, his head would nod ever so slightly to watch Hans’ hoof. That was the subject’s cue to start tapping. When he tapped an appropriate number, Pfungst would lift his head, satisfied with a correct answer. Again, the subtle movement was picked up by the horse. Anyone wishing to ask Hans a question would likely be expecting a correct answer, and therefore would be an excellent candidate to give strong signals. Pfungst tested his theory further by asking Hans questions from greater and greater distances. The farther away he stood, the more difficult it was for the horse to pick up the signals. Blindfolded, Hans’ brainpower was reduced to that of any other horse.

Pfungst’s experiments with Hans ruined his reputation and put an end to von Osten’s success. Suddenly, the public no longer saw Hans as an intelligent horse. People felt duped, even though the horse still displayed extraordinary talent worth the price of admission. Though it seems hard to believe a horse could read movements and human expressions with such accuracy, Pfungst’s theory was agreed upon by another prominent Berlin mind, Dr. Albert Moll. Moll was neurologist, a founder of the Berlin Society of Psychology and Characterology, and author of the 1889 book, Hypnotism. Moll believed that hypnotism allowed subjects to respond to extremely subtle signs. “Signs that are imperceptible to others,” he said, “are nevertheless perceived by a subject trained to do so, no matter whether that subject be a human being or an animal.” Despite proving Hans was not an intelligent horse, Pfungst cashed in on the horse’s talent with his book entitled The Intelligent Hans.

While all these great minds focused their energies to prove they were smarter than a horse, author Ricky Jay references a scholar who figured out the method three hundred years earlier. In Learned Pigs and Fireproof Women, Jay writes of Sa. Rid’s book, The Art of Juggling or Legerdermaine, which claimed “…nothing can be done [by the horse] but his master must first know, and then by his master knowing, the horse is ruled by signes.”

Von Osten passed away on June 29, 1909 at the age of 70. Hans was bequeathed to Karl Krall, a wealthy goldsmith and an amateur parapsychologist of Elberfeld. Krall took Hans in and educated several horses of his own – two Arab stallions, Muhamed and Zarif, a Shetland pony called Hanschen, and an older black stallion, Berto. Krall even experimented with the mind of a young elephant, Kama. His exhibition of horses came to end with the outbreak of the World War I. The horses were forced to leave the stage and enter the battlefield.

© Marc Hartzman